If you want a real Balinese experience, the last place you should go is Kuta. At least thatʼs what Lonely Planetʼs 2011 travel guide to Indonesia will tell you. The truth is that if you donʼt go to Kuta, you might as well not go to Bali. If youʼre looking for some sort of cultural enlightenment and you think youʼre going to find it by visiting quaint villages with art galleries and holy temples on display, youʼre an a-hole. If you really want to learn what life in Bali is all about, you have to see it from all angles. You have to venture into the heart of the corruption, chaos and grit in the same way you would immerse yourself in the beauty, serenity and culture. Bali’s rapidly developing tourist industry is a hot topic, and in order to fully comprehend the gravity of the situation, you have to do your research.

Of course, this is all hindsight. When I made a bee-line for Kuta, it was because I wanted to cash in my tourism dollars for an endless summer. Fortunately, my selfish motives revealed a silver-lining. Anyway, experience is the best teacher. Without further adieu, here’s mine.

Sept. 13, 2011 Ascending upon the Island of the Gods

Stumbling through customs partially asleep and half drunk courtesy of Korean Air’s complimentary beverage service, we arrived in Bali at approximately 2:30 a.m. on Indonesia’s clock.

After 28 hours of traveling across Florida, Georgia and South Korea, KC and I had finally reached Denpasar airport, our final destination. For me, it was like returning to a dream. For KC, it was a shocking reality. Still, Kuta accepted us both with the same warm embrace.

Just as I had done 18 months earlier, I hopped in a Bluebird taxi and asked the driver to take us to Poppies II and Benesari Lane, terimah kasih. Twenty minutes later we arrived at Suka Beach Inn, our new home sweet home.

Casey and I dropped our bags on the tile floor of our moldy new room and looked around. It was after 3 a.m. We should sleep. Thatʼs what people do at 3 a.m. Thatʼs what people do after traveling around the globe for 28 hours. They sleep.

“So…†I said. “This is Suka. What do you think?†“Itʼs cool. Are you tired?â€â€¨ “No, are you?â€â€¨ “No.â€

Like a sea turtle returning to its original nesting place, I let my natural instincts lead the way. With memories of my first trip to Bali bubbling to the surface, I took KC by the hand and introduced her to the Kuta Vortex.

The first place we went to was my beloved Sky Garden. The “All you can drink Heineken†special I remembered on the ground floor beer garden was long gone, but there were still 5 floors of raunchy fun perfectly intact. Normally I cringe at the thought of nightclub strobe lights and unknown DJs spinning crappy house music mixes of pop radio songs, but Sky Garden is the exception. You see, on the bottom floor, where all of the ʻlow-keyʼ stuff happens, thereʼs a bar and a beer garden. Depending on the day of the week, youʼll find all-you-can-eat sushi or chicken wings, live music, ESPN, two-for-one cocktails and V.I.P seats to people-watch on Legian Street.

When the bottom floor gets boring, I usually go straight to the top, the Sky Garden. This is where youʼll find the free drinks, the jumbo speakers, and of course, the action-packed sky terrace. The terrace offers a reprieve from the heat with a cool breeze and a hazy view of the city lights. Then of course you have the go-go dancers and projection screens to entertain your thoughts if the city lights aren’t enough.

When happy-hour finally ends, in which case youʼre too drunk to drink anymore anyway, you move down to the fourth floor. This is where the fire dancers perform. Back in the states, this kind of entertainment might set you back more than 100 bucks, but here in Indo, it’s complimentary with your free drinks. The fourth floor also showcases pole dancers bathed in gold glitter and dressed in sequin bikinis. Iʼd never paid much attention to them until I woke up one morning drenched in gold glitter without explanation. It wasn’t until 3 days later when I went on the stage to talk to the DJ that I noticed the shimmering specs fluttering from the dancers.

On the third floor, the “disco stage” is the main attraction. With a magical little disco-ball glittering mightily from the ceiling above and a neon-light installation in the background, the disco stage sits right behind the bar, situated high enough so that you can look down at the tops of the bartendersʼ heads. In a backdrop of blushing red bricks and blocks of lime green, hot purple and cloudy, electric blue glowing here and there, you can’t help but feel like a cartoon. Once youʼre up there for a few minutes, itʼs easy to forget youʼre on display for the whole bar. Your natural instincts lead you to do the robot, the shopping cart, the sprinkler or something equally stupid. You wonʼt even realize that youʼre doing an Irish jig to a Snoop Dog song until your beer is empty, and

reality creeps back in as your attention focuses on the bar below, lined with spectators. But the thrill of ballet dancing to an AC/DC song, river dancing to RHCP, Kryp walking to Hot Chip, and doing the hand jive to Bob Marley – all of which has been done on the disco stage – outweighs the embarrassment.

Once you’ve lost your dignity on the disco stage, it’s probably time to go to Eikon or Apache, or at the very least, it’s just time to leave. Of course, there’s still one more level, the second floor, but as far as I can recall, I’ve never actually spent time on this floor. I believe it has two different bar areas and a few balcony dinner tables, maybe a fountain or a fish tank or something aquatic, but I can’t say for sure. After descending three consecutive floors at Sky Garden, you’ll be lucky to find the door let alone to navigate through yet another level.

On our first night, KC and I decided to go to the infamous ‘Bounty’, a raunchy pool-hall/karaoke-club/ pub-bar/night-club hybrid where almost anything goes. I spent a lot of time here on my first trip to Indonesia. This party palace is complete with ramps and winding staircases that lead to lots of dark corners and mischievous shadowy spaces. At the entrance, first-timers who don’t know any better get a head band to wear. It’s white with big red letters: I WENT TO THE BOUNTY. I wore one my first time, and so passed on the tradition to KC.

Anyway, the first floor is home to a karaoke stage, a separate platform with a pole for climbing and dancing located in the middle of 10 or 15 high-top tables, as well as two bars and a pool table. From there I’ve always gone straight to the top. I don’t even know if there are floors in between, but I can tell you it takes a few minutes to get where I wanted to go: The Bird Cage stage! Zig-zag up the ramp, stumble up the stairs, wind a corner, stumble up some more stairs two at a time, use the handrail to pull yourself up another set of ramps and spiral steps and you’re at the top. This is possibly the most obnoxious place in all of Bali, if not Indonesia, if not the world.

Here you’ll find a main stage with two giant yellow birdcages on either side. Inside the cages, you will encounter anything from naked men with bunny rabbit masks to professional dancers wearing neon lingerie to awkward orgies between sloppy, drunk foreigners. There are two other round stages in the middle of the dance floor, perpetually over-occupied by the sweaty flesh. There are three different bars inconveniently scattered about the scene that serve anything from fish bowls, to 12-inch Arak Attacks, to boots of beer. Fog, strobe lights, lasers, disco balls dangling from the ceiling, music so loud you can’t even hear it. It’s painfully enjoyable combination of sound, light, movement and consumption if you’re in the right state of unconsciousness.

On this particular night, at approximately 4 a.m. though, the place was nearly empty. I gave KC the general rundown, and we moved on. I can’t remember exactly where else we went, but I’m pretty sure I managed to show KC all of the essential venues before we officially blacked out and ended up back at Suka. To this day, I still do not know what time Legian Street shuts down because I’ve never been conscious when it’s happened.

Anyway, welcome back to Kuta.

Sep 17, 2011 I Love Lombok

After 28 hours of traveling across the globe, 36 hours of heavy drinking and 4 hours of sleep, the next logical step was to take an overnight trip on a death-mobile into the heart of Nowhere. My friend Mat (an Australian I met through a mutual friend during my first trip to Indo) and his boring Swedish trio were making a trip to Lombok, and he’d stupidly invited us along. All we had to do was learn how to drive a motor bike on the wrong side of the road without a license at 9 p.m. in slaughterhouse traffic, and then follow him and his weird friends into the Indonesian jungle. We accepted the invitation.

Forget the fact that I don’t have travel insurance, and I’ve never driven a scooter in my life. No big deal that the bike I’ve just rented from a stranger is missing a side mirror, the fragile looking helmet that came with it is probably laced with lice and fresh sweat, and that I don’t know a single thing about Indonesian traffic laws or road rules. “Do I need some kind of license?†never crossed my mind until I was fumbling for my registration and paying off the polisi. Who cares that if I get lost I probably can’t get directions because I don’t speak Indonesian, and I can’t even pronounce the name of the place where I’m going. Not to mention I’ll be sharing the road with what is essentially one massive Hell’s Angel biker gang. Oh, and we’re in a hurry.

I didn’t know how to use my turn signal or where my horn was until 20 minutes into the trip when we had to come to an abrupt stop for a U-turn, and I had to improvise or die. Luckily, I’m lucky. Any sane person probably would have gotten a thorough run down of these critical features, but we were in such a hurry that I didn’t have time to worry about things like safety. When the time finally came to consider these things, I was sitting at a median in the dark in between a slaughterhouse of dump trucks, taxis, and bikes weaving all over the road, lights beaming and streaming by in a dizzying streaks. When I finally managed to make the turn with the help of two Indonesian men, I realized I was lost, separated from the group because I’d taken too long to make the turn. That’s when I realized I didn’t have the slightest idea who to call or how to call them. Then I saw Casey pulled over on the side of the road, looking just as terrified as I felt with her little, white helmet and her thick, black goggle glasses pressed into her face, the buzz of the traffic nearly blowing her off her scooter.

We managed to get back on the road and immediately pulled in to what we thought was a gas station. That last conversation we had with the boys was about getting gas for the bikes, so we assumed they would stop at the nearest gas station where they would hopefully wait, realizing we were gone. All we could do was take a chance because neither of us had a phone, and even if we got our hands on one, I didn’t know Mat’s phone number and his phone was dead anyway. We decided to take a shot at the road again and stopped at the next gas station, luckily just a few minutes away. The boys were lined up at the entrance, looking worried at first and then annoyed.

In Matias’s neat Swedish accent, “Mat just turned around to go and look for you.â€

So there I was, single-handedly sabotaging the whole trip. Not only was I slow, but I got lost, which then forced Mat to get lost which then created a giant clusterfuck. No pressure, but basically we had to make the midnight ferry in Padang Bai or we’d be stuck for about five hours until the next one. I don’t just mean that we’d have to sit around and wait though. I mean we’d have to turn around and make the two hour trip back to Kuta because apparently this harbor was too dangerous for us to stay at overnight. Mat had tried to plan for our handicap, but our initial plan to leave at nine had failed, and we left half an hour late, cutting our allotted learning curve time in half.

Being that I’ve never driven a scooter, every maneuver was difficult for me unless I was going slow, going straight and the road was smooth. This was basically never. The roads were blanketed in gravel and dirt, sprinkled with potholes and stacked with other motorists. Turns were a nightmare not only because I wasn’t used to the throttle, but I was also struggling to get the hang of using the turn signal at the same time. You see, the throttle is on the right handle along with the headlight switch and the back brake, but don’t use the back brake unless you’ve already braked with the front brake, which is on the left handle next the turn signal button and the horn. To use the turn signal, slide the switch in the appropriate direction and then push the button on top to switch it off. So in short, in order to turn I needed the throttle, the brake and the signal. It doesn’t sound like that much to remember, but factor in the mortal danger of fucking it up and you might have a mild panic attack. It was like a real life game of Frogger. To get through this intersection, you have to dodge the oncoming semi truck, and hold your own between the motor bike to your left and the car to your right. To do this, you’ll need to switch your blinker on at the appropriate time, punch the gas at the right moment, hit the brakes at the last second and do your best to gently guide the whole bike sharply to the left with the flow of traffic without jack-knifing. All the while, you’re gripping your crooked handle-bars, clinging to life and praying that you don’t accidentally squeeze the throttle too hard and die. No worries though.

Oh, except that the boys didn’t know how to get where they wanted to go. At any given time, we were never completely sure that we were going in the right direction. It was trial and error. The boys would either come to the consensus that, yes, this looks familiar, or no, we should have turned the other way, I’ve never been here before. It’s not exactly easy navigating a maze of dirt roads with an Indonesian road map that you can’t actually read while trying to spot non-existent road signs in a span of scenic stretches that all look identical.

Every time we pulled over and had to turn around, I would look at Casey and just shrug. All we could do was keep driving and hope for the best. Every time we successfully made a turn or survived an intersection, even in the wrong direction, I was thankful to be alive. Mostly I was thankful that Casey hadn’t totaled her bike yet. If she could manage to fall off of the stage at Sky Garden, wrecking a motor bike was certainly within her reach.

And so there we were, two American idiots, somewhere in the heart of Bali in the middle of the night, cruising down winding roads, careening around blind corners and edging gravel shoulders on motorbikes we didn’t know how to drive, following a pack of Swedish strangers and my one Australian friend into the abyss.

Turns out we made it to the ferry just in time. After paying off the polisi at the harbor on some bogus (or maybe not) charge, we bought our tickets, rode onto the ferry and started floating. Once we were off the bikes I felt generally relieved, but for Casey, it was a whole new panic attack. Out of 100 passengers, our crew was the only foreign entity. A sea of dark faces, heads turning, eyes staring – everybody look at the tourists! This is where we would sleep.

We headed to the top deck with a stack of mats. The roof was empty with the exception of four Indonesian men, heads turning, eyes staring just like everyone else. We laid down and the boys all fell right to sleep, but I was too wired for that noise. While Casey was hyperventilating over the giant rats scurrying across the deck in front of us, I was trying to figure out what steps I’d have to go through if someone stole my backpack. Where’s the embassy? What if they lock me up, and I don’t have any I.D. to prove that I’m me and I get stuck here for hundreds of years? How long does it take to get a new passport? I hope my bank believes me when the thief empties my account and I’m left with nothing but credit card bills for things I didn’t buy. Just when I was about to fall asleep with these happy thoughts, Casey squeezed my arm and I opened my eyes to see an Indonesian man ever-so-slowly making his way toward us. This was it. It was really happening. He was coming to steal my shit. I sat up and he walked to the railing and then quickly turned around and left.

“Tiffani, what was that guy doing?â€

“He’s definitely going to jack our shit as soon as we fall asleep.â€

For the rest of the night I fell in and out of sleep, using my backpack as a pillow, my bright orange Bintang towel as a blanket, and spooning with Casey in an attempt to protect my possessions and stay warm.

The next morning I was exhausted, but I was feeling better about the two hour drive we had ahead of us. It was daylight, and I was finally getting the hang of the bike. Just when I was feeling a little more confident, Casey wrecked. It was an hour and a half into the trip, in the middle of some obscure village, on a narrow road littered with rocks and pot holes. We were speeding up, making our way around a truck in between another motorbike when she suddenly lost control and veered off the road. Her helmet jiggled and bounced as her head knocked back and forth from the uneven ground she was now speeding over. I watched her legs fly out to either side, and I heard her scream just as I sped past her on my bike, unable to stop and help. I glanced back just in time to see her bike tip to the right and skid out of control into a cloud of dust. Casey was dead! Oh my fuck, this was it! After years of somehow managing to survive despite her accident-prone tendencies, her luck had run out. My dear, sweet friend of 12 years and counting. My middle-school BFF, my “she’s one of the familyâ€, always there when you need her, knows everything about me, won’t ever leave me hanging friend of friends. My travel companion and partner in crime, dead on the side of the road.

My heart fell into my stomach. I’ve never in my life felt such a sober hysteria overtake me. It was a stable panic, a level-headed taste of terror, a general feeling of drop-dead, gut-wrenching, “is this really happening,†“this is is really happening,†“WHAT THE HELL!†By the time I had managed to slow my bike down and found a safe place to pull over, there was a mob of people on the side of the road. Traffic was backed up. Locals were coming out of the woodwork, and kids on the their way to school were running over and joining the crowd. Through their legs, I thought I could see Casey sitting up. She wasn’t dead!

I took a deep breath and turned my bike around. I wanted to run over to her and push everyone out of the way, but was partially paralyzed and still fighting the weirdly calm hysteria I was experiencing internally. I didn’t know how badly she was hurt, but I was sure we would need to find a hospital. If she wasn’t dead, something was definitely broken, popping through her skin or gushing fountains of blood.

I walked over to see her sitting on the ground, covered in dirt. No protruding bones, a little blood, covered in dirt. You know, the usual. If I wasn’t paralyzed, I would have laughed, but instead I just stared at her. Johan and Daniel were by her side looking worried, and the locals were inspecting her bike. The headlight was busted and what was left of the plastic side panel was wobbling awkwardly near the kick-stand, but other than that the bike was fine. Typical Casey. From then on, it was smooth sailing the rest of the way to Lombok. We moved at the pace of a sloth, but we all made it there alive.

The Kids of Kuta Lombok

So the first thing I want to tell you about Kuta, Lombok is that you should avoid it at all costs if kids are not your cup of tea. I learned this the hard way. Your Lonely Planet guide probably won’t tell you this, but the place is teeming with rabid, feral children. I’m talking about rampant gangs of tiny people between the ages of 4 and 10 years old, mauling tourists and being incessantly annoying. Ankle-biters who will stop at nothing to force you into buying something you don’t want for a price that isn’t worth paying. Take Lisa for example. Lisa was the first charming, little Indonesian girl to introduce herself to me. She was absolutely adorable, and she was also a liar.

You wouldn’t expect a 10-year-old wearing a pink Chip ‘n Dale T-shirt, Lamb-Chop capris and rubber flip flops to be a con artist, but that’s what she was.

“Hello Miss! What your name?â€

“Oh hi! My name is Tiffani. What’s your name little girl?â€

“My name Lisa. Nice to meet you Stippani. You bary beautipul girl. When you arrive here?â€

“Terima Kasih. You’re very pretty too. I arrived today.â€

“Welcome to Lombok. I hope you like it bary much, and have bary good times on my island. Where you come from?â€

“I’m from America.â€

She flashed a toothy smile and her eyes lit up.

“Ohh-baah-maah!â€

I was impressed. Not just that this young Indonesian girl was already bilingual at an age when I was just learning to ride a bike without training wheels, but that she was such a polite child, perhaps the first one I’ve ever met. I certainly couldn’t name the president of Indonesia, or the king, or dictator, or prime minister or whoever it is that runs the country. I felt like an idiot in the presence of this remarkable kid.

That’s when another, tinier, even cuter kid showed up. Lisa introduced me to her little brother Junari, a miniature four-year-old carrying a wooden board dripping with homemade jewelry and gripping a broken Transformer toy. And then three more kids materialized behind Junari. They were multiplying fast.

Casey came over to see what was going on, and within seconds we found ourselves sitting on the steps of our homestay surrounded by a handful of beautiful, well-behaved, happy Indonesian kids trying desperately to sell us some very ugly merchandise. Being naive tourists, we played along with the kids, letting them show us their creations and tell us their names and ages etc, etc. Then the conversation moved from casual to business.

“So you want buy bracelet for good luck? I gib you bes price. I have many color.†Lisa winked and smiled.

Junari handed her a wooden board with her name on it. It was dripping with shells on strings, Lisa’s good luck charms. The bracelets were generally unattractive at best, made from the kind of loose string you would pull from a worn-out sock. They were decorated with generic plastic beads and small shells that will get you arrested if you try to take them through customs. The main color scheme is spaghetti-vegetable vomit: red and brown strings laced with murky pink and moldy yellow beads, bits of olive green plastic shards and a few brown shells in the shape of fresh dog poo. In conclusion, I wanted nothing to do with Lisa’s beautiful bracelets though I admired her spirit.

“Oh no thank you. I don’t need any bracelets.â€

“You buy one for good luck! Bes price from Lisa.†She winked and smiled again.

“No thank you. They’re very nice, but I don’t need one.â€

“Maybe tomorrow you buy? If you want buy bracelet tomorrow you find Lisa okay?â€

“Okay, maybe tomorrow Lisa.â€

I had no intention of seeing this kid tomorrow, or ever again really, but the next day, there she was. Lisa and her little gang waiting on the front steps of my homestay.

“Hello Stippani, Today you say you buy bracelet.â€

Just then, another young girl showed up with her own gang of tiny kids.

“Hi Miss. You bary beautipul. Where you from.â€

Before I could answer, Lisa crouched down and growled at the newcomer. The other girl hunched her shoulders and growled back. I felt like an injured deer lying between two hungry wolf packs. There was a moment of silent tension and the newcomers retreated. Lisa turned back to me, winking and baring her teeth.

“Okay Tippani. I gib you dis bracelet for five thou-send.â€

“I thought you said 1,000 yesterday.â€

“No good for me. Business bary bad. Five thou-send good for me, good for you. Bary cheap.â€

“I’m sorry Lisa, but I don’t want a bracelet.â€

Her voice went from a giggly squeak to a deep moan.

“Yesterday you tell me today you buy. You promise.â€

I hadn’t promised this kid anything, but I felt like an asshole anyway. Five thousand Indonesian rupiah is the equivalent of 75 cents. I didn’t want a bracelet, and I didn’t want to condone this behavior, but 75 cents seemed like a cheap price to pay to get rid of these werewolves.

“Okay Lisa, here’s the deal. You make me a bracelet tonight, just like the one you’re wearing, and I’ll give you five thousand instead of one thousand.†She was wearing a red and white bracelet with her name weaved into it. “No shells, no beads. Just string, and you make it say my name instead.â€

Her voice went back to normal, and her big, doughy eyes bulged out of her head. “Oh yes, Tippani. Yes okay. Many color. How many color you want. Maybe red, blue, purple?â€

“How about green?â€

“Oh yes. Green. Very beautipul. I make green for you.â€

And so, I wrote my name down on a piece of paper and Lisa and her pack disappeared down the road.

The next day when I woke up and went to get my breakfast, Lisa was sitting on the steps with a pack of 10 children, making my bracelet. As I walked over, a little girl who I’d never seen before stopped me in my tracks and wrote my name in the sand with a stick, smiling sweetly. Junari sprinted over and pointed to it. “You Tippani.†He sprinted away again. He did this about four times before I had the strength to ignore him and make my way over to Lisa. I guess the kids were cute or whatever, but I’m not a kid person, and I hadn’t even had breakfast yet so I wasn’t ready to deal with all of this asinine behavior. I just wanted to get my goddam bracelet and get rid of them.

I sat down next to Lisa. She winked and bared her teeth. She was just finishing my bracelet. It was not green. It was red. The color of ketchup. The only color in the whole world that I actually dislike. It was the same color red as the bracelet I’d seen around Lisa’s wrist the day before, the bracelet that was now missing. This little twerp had taken her bracelet apart to make mine. If you think that’s a sweet gesture, it’s not. It’s not sweet because it’s not what she was forcing me to pay for. Meanwhile, there was an army of kids hovering around me, asking questions, leaning on my shoulders, giggling and sucking their thumbs and doing all the other gross, weird things that kids do when they’re too shy to actually speak like normal human beings.

I waited patiently for Lisa to finish, trying to tell myself that it was no big deal. I didn’t have to wait long though because Lisa ran out of string, which meant my bracelet was finished. Without asking, she began tying the unraveling thread to my ankle and lit the end on fire to stop the fraying. I didn’t know what to say. There was a sharp, white plastic band sticking out of the end where she’d run out of a string, and it was stabbing my ankle bone.

“Okay ten thou-send please.â€

“Ten thousand? You said five thousand yesterday. You said one thousand the day before. That’s not fair. I’ll give you five thousand.â€

“No, you silly Tippani.†She winked and bared her teeth. “I say five thou-send ip you buy one like dis.†She pointed to the shells on strings. “My price for dis one is twenty thou-send, but I gib you for ten because it bes price.â€

“No Lisa. You told me five thousand. I have five thousand right here in my pocket. That’s all I have.â€

Her voice lowered three octaves. “You pay me ten thou-send. I gib you bracelet. You pay me!â€

I looked her square in the eye and leaned forward. She crossed her arms and stared back.

“You lied to me, but you know what? I’m going to go to my room and get you ten thousand rupiah, and then you and your friends have to leave. You can’t come back here, and you can’t bother me anymore. If I pay you, do you promise you won’t bother me or my friend anymore?â€

“Ya.â€

I went to my room to get my money. For a split second I felt like an a-hole again. I had just gotten into an argument with a child over a buck-fifty. That feeling went away instantly though, when I thought about what a nefarious operation this girl was running. She wasn’t sweet or polite or well-informed. She was a thieving, scheming con.

When I sat down at the breakfast table, Mat’s Swedish friends were sipping mango milkshakes and nibbling on fresh papaya. Matias had a bracelet tied to his wrist.

“Matias, where did you get that bracelet?â€

“I get this from the kids you were talking to. I get mine yesterday. I feel bad, so I bought one, but I don’t like it so much. I just wanted them to go away.â€

“How much did they make you pay?â€

“I paid three thousand to a little boy, but then I had to pay three more to his sister or something.â€

I have to say though, at least one good thing came out of this experience. Thanks to Lisa, for the rest of my time in Indonesia, I had no trouble telling kids to beat it, scram, get the heck out of here.

It was actually the very next night, less than 36 hours later, that I saw Lisa again. Casey, Mat, the boring Swedes and myself were sitting down a wood-fire pizza dinner at a little shop down the road. We’d just gotten our Bintangs and placed our order when Lisa showed up with her crew. I watched her walk in and stop at the nearest table. She was winking and smiling at an Italian couple, and the other kids were crowding around the table, giggling and smiling and being weird and gross and kid-like. A few minutes later, another gang showed up, and then another. Three different mobs of kids were now present.

Lisa lead her gang to our table.

“Lisa, I paid you yesterday, and you promised me you would leave us alone. We don’t want any more bracelets, no more stuff. It’s nice to see you again, but we’re eating dinner, okay? Have a good night.â€

“Lisa no remember,†she hissed. Then she turned to Johan with her human voice, “Hi boy. Where you from?â€

I didn’t give him a chance to speak. “Lisa. I bought a bracelet from you. You lied to me, but I paid you anyway. You have to leave.â€â€¨ “Lisa. No. Remember.â€

Casey chimed in. “I was there Lisa, and I remember. No more stuff.â€

“I no remember!†she shrieked. “You buy!â€

Mat slid his chair away from the table and turned to face her. “We don’t want your shells on your on strings. You got that? Now beat it breadroll.â€

“Maybe you buy tomorrow? You bary handsome,†she said in her sweetest voice.

“Maybe I buy never. Get out of here.â€

That was the last time Lisa bothered us. Not to say that I never had trouble with any of the other kids, but I dealt with it much more efficiently. I will admit that every now and then I feel a tiny bit bad about refusing to give buy those ugly bracelets from the Lombok kids because at the end of the day they’re just kids doing what they’ve been taught to do. Still, money doesn’t grow on trees, and if I went around accepting every sales-pitch that came my way, I’d soon be selling my own bracelets.

I shot the tourist

Despite the fact that Lombok is overrun with feral children, it does have a few redeeming qualities, like adults. Most of my experiences with locals were generally non life-threatening, if not completely pleasant. Our homestay staff, which was run by a local that Mat had stayed with on a previous trip, was very hospitable. The owner, G’day, gave us decent prices for the rooms as a favor to Mat. I’m sure it had nothing to do with the fact that Mat and three of his friends had all of their possessions stolen from G’day’s previous homestay. I chalk it up to G’day just being a nice guy. And then there was Lee, the guy in charge of the place while G’day was doing business elsewhere. He was a quiet, courteous man, no taller than me and probably in his early 30s, who kept everything running smoothy. He served our food and beer, kept track of our tabs, cleaned the pool daily and watered the gardens excessively. He helped Casey get her broken motorbike fixed, told us the best spots to watch the sun set and offered us rides whenever we might need to go anywhere. His wife cooked our meals and was always happy to see us, holding her son by the hand and making him wave like only a mother would do to an infant. Overall, they were a friendly bunch of Indonesians.

There was one in particular who was actually too friendly. His name was Robby. We met Robby the very first night we stayed in Lombok. It was sometime around 9 p.m. and we were all sitting by the pool, sipping Bintangs, listening to music, just hanging out. Then Robby arrived in full cammo gear, sporting a thick mustache and a cammo baseball cap.

He bummed a cigarette off of Casey, a light off of Mat, a swig of whiskey from Johan and parked himself on the edge of the pool. He spent the next 10 minutes trying to coax us into going to a party, “api, api†in Indonesian, enticing us with mushrooms, bonfires, sexy people. Finally, he left. A few minutes later though, there was a blazing fire behind our homestay. Robby came back.

“I make you fire. You go api api. Make party time.â€

Within minutes, the Swedes had gone to bed, Mat had gone to take a shower and Casey was in the homestay kitchen getting us another round of beer. It was just me and Robby.

I was laying in a patio chair and Robby was still at the edge of the pool in front of me. He was hunched over with his legs spread, elbows resting on his knees, hands dangling in front of him.

“You want api?â€

“No, I think we’re getting up early tomorrow. No api tonight.â€â€¨â€œMaybe you come with me.†He was whispering and slurring his words. “I gip you money.†He swung his hand toward his dick like a monkey scratching its balls. “You come with Robby.â€

Just then Casey came back with the beer.

“No, we’re tired. We have to go to bed. Goodnight Robby. Casey, say goodnight to Robby, we’re going to sleep now.â€

For the next seven days, we were afraid to even whisper Robby’s name, because usually he would appear. He’d told Casey and I that he was pool security, and he told Mat that he was night security, but he was everywhere, all the time. We’d see him during the day gardening or moving piles of rocks around, shining motor bike parts or clinging to the top of a palm tree hacking off fronds and coconuts. At night, every now and then when we were watching a movie with the door and windows open, we’d see a flashlight pacing back and forth by the pool. We knew it was him. There was no one else it could be. Robby also had a dog that followed him around, just as creepy and overly friendly. The thing would bark at us the minute we tried to leave the homestay, but then it would follow us wherever we went, stopping at the internet cafe or eating lunch at a food stall or just walking the beach. Every morning we’d wake up, and the dog would be lying directly outside of our door, waiting to accompany us to breakfast. We never actually saw the dog interact with Robby, but there is no doubt that this was his animal.

The last time I saw Robby was the day before we left when a birthday celebration paraded into our homestay garden. Apparently, when a kid turns a certain age, there’s a celebration that parades the kid around on a wooden horse, all through Kuta, stopping here and there to play music and show off the birthday boy or girl. The locals dress up in their nicest sarongs and pull out the tambourines and speakers and march around in the midday sun. On this day, Robby was wearing a barong, which is just a male sarong. Casey and I were sitting outside our room reading when he approached. From the time he said “Hello†to the time he finally left us alone, he was fidgeting with his crotch area under the barong. This would have been absolutely inappropriate, except that just a minute after he greeted us, he lifted up the front of his barong, and we were able to see his drawstring pants underneath. To this day, I am certain Robby was just trying to tie his drawstring in a bow under there.

I did manage to meet one other overly friendly Indonesian guy, but this was guy was friendly a strictly friend kind of way. His name was Agus and he was from Jakarta. He was actually traveling through Bali and Lombok with a Hawaiian family, taking them to the best surf spots and shooting photos for them. The first day I met him at our homestay. He was sitting at the counter, looking through some digital photos on his very nice, expensive Canon DSLR. I asked if I could have a look. His photos were pretty good. The next day I saw him again at Mawi, a remote surf spot about an hour from Kuta. I’d ridden on the back of Mat’s bike, so I was able to bring my camera, but all I had was my standard lens, and the boys were surfing pretty far out. Without hesitating, Agus handed over one of his extra lenses. This is kind of a big deal if your a photographer. Lenses do not come cheap. It’s not the kind of thing you just hand over to a stranger, not just because there’s a chance you’ll never get it back, but because there’s a chance that it will come back broken. What’s more, Agus let me take the lens back to G’Day’s when I left, telling me to go ahead and use it for a few days. If that is not a trusting, decent human being, I’ve never met one.

In general, I guess you could say that most of the locals seem pretty friendly, but sometimes, their toothy, plastic smiles can make the hair on the back of your neck stand up. For example, when you’re enjoying dinner at a tiki bar on the beach at sundown and a Bob Marley CD is playing in the background. You’re sipping a frothy Bintang and cracking jokes and soaking up the local charm and watching the children hassle passersby in streets. You smile at a group of Indonesian guys sitting at a table across from you and everything is just wonderful. Until only one man smiles back, beaming like a Cheshire cat. The rest just stare at you, expressionless. The friendly one is swaying back and forth, singing along with Bob to ‘I Shot the Sheriff.’ But the words are off. He’s singing something different. You turn your head slightly to get a better earshot. He waves to you, still smiling and singing. While you’re waving back, you catch the chorus. “I shot the tourist.†Good thing I hadn’t read that Lonely Planet guide until after I’d already been here, or I might’ve been worried. According to the Bali, Lombok edition, tourists have been held at knifepoint and robbed by these smiley locals. At the time, I didn’t know that, and it was only slightly unnerving.

Then of course, there are the locals driving dump trucks and motor bikes who will swerve off the road just a few feet in front of where you’re walking and scare the living shit out of you. Just before you break into a full sprint or dive behind a pile of rocks, they swerve back onto the road, slowing down to point and laugh as they pass you. Aside from this, I guess they’re all pretty fucking wonderful. Right.

The Art of doing nothing

Once you’ve got the swindling kids, volatile locals and too-friendly friends under control, you can relax and enjoy all that Kuta, Lombok has to offer, which is essentially nothing. No really, it’s a way of life here. Aside from surfing, eating, drinking and sleeping, you won’t find very much going on. Just basic needs being met on a daily basis. Sometimes you’ll see traces of something happening, but never the actual undertaking. Maybe there’s a wooden frame for a house under construction, a motor bike engine half dismantled, or a big hole in the road with a pile of rocks and a bunch of shovels and hammers laying around it, but it’s a static scene. There are plenty of locals hanging around the place, but they’re sedentary, sitting still just staring at the thin air and watching the wind blow. You’ll see them leaning against trees and motorbikes, sprawled across porch steps, dangling loose limbs over the edges of hammocks, rigid bodies planking wooden benches or even just sitting in the dirt on the side of the road. No broken down motorbike or vehicle around, no visible accident or injury, not much scenery or much of anything to observe, just some Indonesian dude sitting in the dirt on the side of the road doing absolutely nothing. I think the kids selling bracelets are the only ones who actually do anything in Kuta, which is a shame, because they’re the ones that should be sitting still in the dirt on the side of the road, minding their own business and leaving everyone alone. But anyway, like I said, doing nothing is a way of life here. So, when in Rome …

I will warn you though, doing nothing sounds easy, but just every other aspect of Lombok and of life itself, there are pros and cons.

When doing nothing consists of slipping into a coma of Tim Tams and Bintang, it can be quite nice. Laying in the shade reading Slash’s tell-all biography about life with Guns ‘n Roses while you’re sipping a thick, banana milkshake, or just laying on the hot stones next to the pool, listening to the Black Keys, Caribou and Bonobo with the sun beating down on your skin and your Bintang sweating in its coozie. Every moment is effortless and easy. From the time you wake up to the time you fall asleep, your only role in life is simply to exist. Sometimes you wake up early, sometimes you wake up late, but it’s always the right time for a Mie Goreng or banana pancakes. It’s never too early to crack a cold Bintang, never too late to have an Almond Magnum ice cream bar dripping down your elbow. Saying it’s time for breakfast, lunch or dinner is just a universal way to say you want a massive meal, not just a massive snack. Time is irrelevant. You eat, sleep and drink based on impulse, craving, and hunger. The day of the week is irrelevant too. It’s always just, ‘today,’ and everything either happened yesterday or the day before. Yesterday I spent 8 hours floating in the pool, sipping Anker and learning how to swear in Norwegian … or was that the day before? Otherwise, the day of the week depends on how you feel. Usually, every night feels like a Friday night, and every day is like a Sunday afternoon, and nobody questions it. Doesn’t matter if it’s a Monday or a Friday anyway, because it’s a beautiful day for the beach and its the right kind of night for a Mark Wahlberg marathon: Shooter, Fighter and Four Brothers back to back, in bed with a bucket of melted Tim Tams, a few pounds of Pringles and a handful of chocolate pies. Maybe before the marathon, we’ll take the motorbikes down the road to watch the sun go down over the mountains. Tomorrow, we can do it all again. Nothing but sunshine and candy.

Sometimes, if you’re feeling ambitious, you might wake up early and go for a surf. Maybe just go down the road to Gerupuk and a take a short boat ride out the outside break. Or maybe you’d rather go to Mawi. It’s a lonesome beach tucked between two cliffs, about an hour away from Kuta. These are the places, the waves, the experiences that surfers everywhere come to Indonesia for. And if you’re not a surfer, which I’m not, these are still the places, the waves, the experiences that anyone comes to Indonesia to appreciate.

To get to Mawi, you follow a solitary ribbon of gravel road through a rolling, sweeping, earth-toned panorama, and you don’t stop driving until you’ve reached a deep, swelling sea of turquoise surf. Unless you need more petrol, which you probably will. In this case, you have to keep your eyes peeled for signs of life hiding in the brush. There are a handful wooden huts scattered along the dirt road, most of them leaning to one side with a rainbow of drying laundry hanging on the porch and thick, grey-brown smoke pouring out of the windows. What you’re looking for is the wooden lean-to with a the cart of liquid gold sitting out front. There’s only one place you’ll find it, 35 cents per bottle, so when you see it, you better buy it right then and there, because you won’t find petrol for miles otherwise. More frequently, what you’ll encounter are clusters of school kids bumping into each other on the side the road, wearing bright purple and burnt orange uniforms, lugging sacs and packs and baskets of pineapples in the direction you just came from, which is a mystery to me because where the fuck did they come from and where do they think they’re going? Same thing with the empty-handed loners walking down the endless road. Where did this guy come from and where is going that is in walking distance? Anyway, now and then a stray goat or a monkey or an entire herd of cattle will cross your path and force to go off the road, but for the most part, it’s just you and whoever you’re with in the heart of a giant, organic abyss. It’s a beautiful, beautiful thing.

After a trip to Mawi, there’s only thing you can do: eat. But not just anywhere. There’s one place in particular, a place whose name I can’t remember with a view I’ll never forget. It’s some sort of vegetarian restaurant that apparently only serves one dish, and that is culinary perfection. Every item on the menu sounds delicious and tastes better. And while you’re relaxing in a pile of pillows with your mouth full, you can enjoy the breeze that comes with the view: this place sits at the top of a mountain that basically overlooks the entire world. It’s another beautiful, beautiful thing.

But before you start getting all emotional about Lombok, let me tell you about the flip side to all of this “Let’s do nothing all day or let’s go for a surf.†Like I said, everything has its pros and cons, and Lombok is especially bipolar.

Just when you think you’ve mastered the art of doing nothing, and you’re all blissed out with your perfect barrels and your Tim Tams and your Bintangs and your DVDs, Lombok unleashes its fury. When I say ‘unleashes its fury’ I actually mean that nothing happens. Absolutely nothing. An empty, sucking, desolate void of nothingness, the kind of nothingness that kills Atreyu in the Neverending Story. I’m talking about losing power. You see, there isn’t enough power to go around the whole island, so they have to sort of rotate the flow from place to place. This means that at any given time you can and will be denied electricity. You never know when an outage will happen, and not even the locals can tell you how long it will last.

The problem is that when you lose power, you lose the will to live. On any given day, it’s about 800 degrees in Lombok, and for starters there’s no air conditioning. The one saving grace is your ceiling fan, which will keep your face from melting only if it’s kept on full blast at all times. In short, no power, no life support. It becomes too hot to live. You have to lay on the tile floor like a dog, barely breathing and gently blinking just to prevent your blood from boiling. Refrigerators lose their cool, freezers leak onto the floor, stoves, microwaves, and blenders become painful reminders of once full bellies and happy tongues. DVD players, computers, phones, and speakers go dead instantly, un-charging themselves at the first sign of an outage.

The worst thing that can happen is a night-time outage, when the island dissolves into a black void. Not only can you not see, do or find anything, but you can’t even sleep through it. The power can go out while you’re in the middle of a coma, and the heat will tear you out of it the second the fan blades slow down. You’ll wake up drenched in sweat, breathing heavy, wishing for death, but it won’t come. Nothing will happen. Maybe for hours nothing will happen. Usually, the sky can sense when an outage will occur, and as a defense mechanism, it gets so cloudy that you can’t even see the moon, let alone the stars. I’m talking complete and total darkness with no escape. You never get used to it, and it never gets easier. All you can do when an outage happens is slow your breathing and pray for power.

So after a week of taking the good with the bad, the over-indulgences with the insufficiencies, it was just about time to get back to real life and actually do something.

Dying to get back

Don’t get your panties in a bunch too quickly though. Where’s the fun in going home sweet home without one last tango with death? There is none! And so, Casey put her life in jeopardy once again. Okay, maybe it wasn’t a near death experience, but it was pretty bloody and a little unnerving.

Fresh off the ferry at Padang Bai, Casey had completely ripped her toenail in half. She’d managed to drive about 4 kilometers down the road before pulling over and panicking.

“I can’t ride this fucking bike anymore. My toe is bleeding everywhere. It hurts, and it feels like it’s broken, and it’s making me lightheaded. I’m dizzy, and if I ride this fucking bike any farther I’m going to pass out and crash. I can’t do it.â€

After surviving 7 grueling days on the motor bikes, with just an hour and a half to go, Casey lost her cool. She had somehow managed to injure herself before we’d actually even hit dry land. On her way off the ferry ramp, she’d gotten her toe stuck in the metal grate, and then in a rush to get out of the way of a semi-truck, she’d hit the gas and ripped her toenail completely in half.

Obviously we weren’t going to keep riding if Casey wasn’t confident she could do it, but then we weren’t really sure what we could do. It was late at night, we were in bumfuck Egypt and the roads were nearly empty. Not the ideal situation for catching a cab. Leaving the bike wasn’t really a problem, but there was no way one bike could handle two bodies and two backpacks. So we sat. We sat on the side of the road, Casey with her head in her lap, Mat and I staring into space, fidgeting with helmets and straps and zippers, and a mangy dog barking its head off all the while. What seemed like a month of Sundays later, we were back on the road, and we didn’t stop until we got Suka. Even when I got lost.

Yep. I got lost. Once again, I was separated from the group, but this time Casey wasn’t there waiting for me. I was on a one-way street, stuck between a dump truck and a pack of motor bikes, and I’d apparently missed the turn. The good news is that I was close enough to Suka that I could find my way by asking around for Poppies II. In about 15 minutes, I pulled in to Suka to see Casey at the front desk looking terrified but relieved.

R.I.P Lombok.

Sep 22, 2011 Kuta Cobweb

After 126 hours in transit over a two week period around Indo, sometimes all you want to do is skull a Bintang and get hectic on the dancefloor … and for 12 days straight.

——

Just in case you don’t remember where I left off in the grand scheme of things, I had just gotten lost at the end of an 8 hour trip back to Kuta, Bali, but had somehow managed to find my way back to Suka. It was something like 9:30 p.m. and I was starving. The problem was that all of the food stalls and most of the restaurants in the immediate area were closed. That is, all but one: Piggy’s. At the time, I didn’t know the name of the place, but I knew from prior experience that there was one place on Poppies II open past 2 a.m. I knew this because I’m a fat American and I’d gone there on several occasions at about 2 a.m. to have a plate of french fries before blacking out. It’s sort of a trashy, Australian-oriented place with Aussie memorabilia lining the walls, a pool table in the corner and AFL games blasting on TV. If there’s no game to watch, the John Butler Trio or Bob Marley is sure to be playing in the background. There’s actually nothing special about Piggy’s except that it’s completely average, which makes it very special. What I mean is that you’re allowed to have expectations. Piggy’s is one of the few places in all of Indonesia where you can order a hot dog that actually comes out looking like a hotdog on an actual hotdog bun. You can order a beef burger that is actually made from beef and is served on an actual burger bun. They have yellow mustard, Bundaberg rum and napkins that don’t disintegrate when you touch them. So this is where we went for dinner. Me with my yellow-mustard hotdog and Bintang, Mat with his beef burger and Bundy rum & coke, Casey with her chicken tenders and Bintang – all served with french fries.

After dinner, things started to go dark. From what Casey and I can recall when we put our heads together and think really hard, is that we all went back to Suka to call it an early night, but at the last second Casey and I had a change of heard and went out without Mat. From there on, all that remains of that night are a few shaky video clips, one vague memory of a late-night door bashing and a couple of healthy hangovers that could only be eased with a poolside Moroccan barbeque.

Meet the Moroccans

One of the slightly filthy but most charming features of Suka Beach Inn is the community bath, also known as the pool. Not only is it good for cooling you off during the day and keeping things hot when it comes to late-night drunken shenanigans, it’s also a social crack pot. You never know who you’ll find there or what they’ll be doing. Sometimes there might only be a few stragglers quietly reading books, but more often than not, there’s at least one hundred people getting absolutely drunk.

On this particularly morning, there were approximately 100 Moroccans accompanied by 100 of their closest Brazilian friends, all feasting and frothing like kings by the pool. I’m talking cardboard crates torn open and dripping with Bintang, a congo line of empties already decorating the perimeter. Smoldering, smoking charcoal-grills waiting to be fed from an adjacent table covered with raw steaks, chicken breasts and sausages. Fresh salads, squishy loaves of warm bread and bottles of tequila materialized to fill in the gaps left by the meat on it’s way to the grill. And of course, to tie it all together, a dangerous tangle of extension cords carefully winding around the pool, leading to a set of speakers that would be appropriate for the top floor of Sky Garden. It wasn’t even noon yet, but my hangover was cured.

I can tell you right now that there isn’t anything better than falling into a cold pool on a hot day, still chewing on a piece of freshly grilled tenderloin and being handed a beer while your head is still underwater. We carried on like this for several hours, until everyone was reasonably drunk and completely stuffed. It was just the right time to head to Alley Cats. Casey, Mat and I were already finishing our first Double Doubles when all one hundred Moroccans showed up screaming and hollering in full Indian head dresses. It was beautiful.

The most important thing you should know about this beautiful scene, is that it’s one of the last that I remember. Immediately following our first round of Double Doubles, Casey and I decided it would be wise to switch to Arak Attacks. It took Casey and I about 15 minutes to come up with the small pieces of this night I’m going to tell you about.

Arak Attack!

So Alley Cats is a bar just around the corner from Benesari, hidden in a back alley. By day, Alley Cats is where you’ll find Swedish meatballs, mashed potatoes with brown gravy, thick lasagna, hot sausages and a whole menu of other hearty dishes, all to be enjoyed while sitting in a lovely courtyard lined with dark, wooden picnic tables. At night, this is where you pre-game after a day of drinking on the beach. What Alley Cats is infamously known for are its Double-Doubles. A Double-Double is basically a vodka-Redbull with a spoonful of rufalin. It’s a lovely concoction that will cost you approximately $1.50, and it will have you completely blind in under an hour. Before taking Casey here for the first time, I remember warning her about how I’d only been there a couple of times during my first trip, and I couldn’t remember leaving the place on any occasion. Apparently this is very common because there was a shirt hanging on the wall that read, “I came to Alley Cats last night, and I don’t remember leaving. Damn those Double-Doubles.â€

In an attempt to defeat the odds and leave Alley Cats in a conscious state, we decided to spring for Arak Attacks instead. An Arak Attack is simply Indonesian vodka, which is made from gasoline and paint chips, and a dash of sprite. We had failed to consider the fact that Double-Doubles were not the only recipe for a blackout, and soon we were downing Arak Attacks like water. Of course, this was not the plan. The plan was to have a couple of drinks before heading to Espresso Bar for some live music. What really happened was that we bumped into some rowdy Californians at the bar who couldn’t wait to shower us with drinks, Mat included. They were two guys from San Diego who were only in Indonesia for the night, flown in to make sure that a rebellious band went on stage in Jakarta as scheduled. Apparently, they had flown all the way to Indonesia, to get that job done from Bali. All I know for sure is that for the next hour, I had an Arak Attack in both hands and couldn’t drink them fast enough.

The next thing I remember is being at Eikon, drinking out of a beer funnel. From there, I went to Apache, where I vaguely remember taking shots of straight Arak with the lead singer of the reggae band and dancing around with Mat for what seemed like hours.

My next memory is of death. I jumped out of bed and ran to the bathroom just in time to projectile bile into the toilet. This might seem like a standard hangover for some people, but puking has no place in my life, hangovers included. The last time my stomach decided to launch itself out of mouth was three years prior to this: It was New Year’s Eve, and it was an involuntary action that probably saved me from alcohol poisoning, yet still managed to deeply disturb me and fill me with regret. For me to wake up out of my sleep and vomit was a serious problem.

But there were other more gruesome details to deal with. I took in my surroundings, which in fact were not my surroundings. I was in Mat’s room. Better him than a stranger I guess. He was half asleep on his death bed, looking worried and sickly.

“You okay?â€

“Nope. Just yuked. Help me.â€

I laid back down, trying to figure out why we’d left the bars early when I noticed something very strange peering at me through the window. It was daylight. Excuse me, but where the fuck did the night go? I was under the impression that I’d tapped out early for a short nap, putting the time somewhere around 3:30 a.m. It wouldn’t be the first time that I’ve disappeared and had a snooze, usually on a kitchen counter or a dining room floor, and then reappeared, just like new, to finish the night off right. Apparently that’s now what happened this time. It had to be at least 7 a.m.

The most alarming thing though, wasn’t the puke, or Mat’s room, or daylight: it was my appetite. I could not eat. Most people puke and then spend the rest of the day avoiding food, which is what seemed to be happening now, but it was a new experience for me. In all my life, I don’t think I’ve ever come across a hangover I couldn’t eat my way out of. Even on the nastiest hangover days, I could wake up and go straight to McDonald’s and devour a pile of hash browns and pancakes with orange juice, and then an hour later I could follow it up with chicken nuggets and french fries, maybe a strawberry milkshake. My favorite hangover food was leftover buffalo wings or cold pepperoni pizza. If those options weren’t on the menu, I’d spend the better part of my day tearing through cupboards, eating anything I could find, but usually I would call around and beg my dearest, closest, most bestest friends to deliver me something or to drive me somewhere, which usually worked. Today, out of habit, I had convinced Mat to snag me a jaffle from the downstairs breakfast area, but it was useless. I was struggling to nibble on a warm piece of bread wrapped around a smushed banana. Can you think of a more delicate food item? It was like acid in my mouth. If this is how normal people feel every time they get a hangover, props to you guys for continuing to get belligerently drunk. That shit is rough.

Needless to say, Arak was quickly replaced with Bintang and Double-Doubles later that night. A few days later, a story was going around Suka, about a girl who was staying there who went to the hospital after taking shots of Arak. Turns out there was ethanol in it.

But anyway, after clinging to life for a few hours, I was ready to begin my day. From Mat’s room, I could already hear the Moroccans by the pool, and I felt my hangover disappearing.

On this particularly sunshiney morning, the speakers were blasting a Michael Jackson remix and the cardboard crates were quickly emptying, the pool was filled with Dora the Explorer beach balls, neon inner tubes, marine shaped lounge chairs, and Nerf toys. There was no sign of a BBQ though, which was just as well because I still wasn’t hungry. That is, until the delivery McDonald’s arrived a few minutes later.

There I was, innocently floating in the pool with a lime green tube tucked under my armpits and a hot pink one around my neck, just trying not to puke, when a thermal bag of hot, greasy McDonald’s opened like a treasure chest in front me. I watched Raf, one of my Moroccan friends, pull out a never-ending supply of golden fries, sloppy Big Macs and sweaty cardboard cups of Coke and pass them around. I’m not sure if it was the pouty look on the my face, or the way I was hovering at the edge of the pool like a starving zombie, but each and every Moroccan made a generous effort to share their bounty with me.

Cosmos tore his Big Mac in half and handed the bigger half to me. Before I could take a bite of it, hands were coming at me from all directions, pushing one, two, or three french fries in my mouth at a time in between sips of Coke and Sprite and Bintang. When the initial frenzy was over, I was set up with a proper buffet: Any and all leftovers were laid out in front of me as I floated at the edge of the pool scarfing down half of Big Mac with two chlorine-soaked hands. Without even looking, my pruned fingers rummaged through soggy bags of warm, salty McDonald’s french fries, tipping over containers of Sweet and Sour sauce and occasionally picking up a chicken nugget. When I couldn’t possibly eat any more I leaned back in my tube and floated to the middle of the pool and let the sun beat down on my face. There was a loud splash followed by a cold Bintang and a friendly face hovering over me. Another hangover was dead and gone.

work in progress, to be continued…

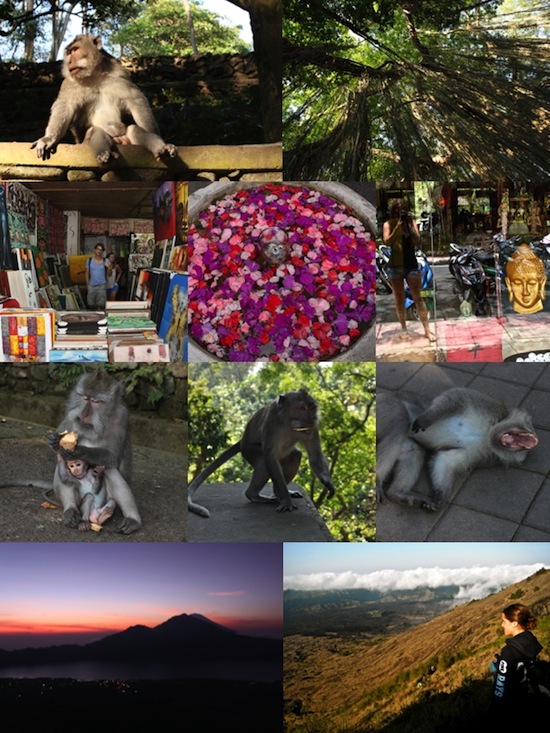

Oct 4, 2011 Beware the Monkey Rainforest

For whatever reason, Casey, Mat and I decided to make a trip to Ubud. One night away from Kuta, but not too far away. Being that none of us had ever been to this highly acclaimed tourist pit, we simply hopped in a cab and let the driver take us wherever he thought we might like to go, which turned out to be Ubud’s main attraction: the Monkey Rainforest. After a 90-minute drive, he dropped us on the side of the road, at the bottom of a hill right in front of monkey sanctuary. After we found a place to stay, we decided to give it a shot.

Let me start by saying that monkeys gross me out. I’m not talking about the tiny circus monkeys that wear red vests and do tricks on miniature motorcycles, or even the big, scary ones that Jane Goodall hangs out with. I’m talking about the dirty, vicious monkeys that live in Indonesia. First of all, they’re way too human to feel comfortable around, especially if you’re trying to feed them. They have the most condescending facial expressions, and they throw around the kind of dirty looks that pierce the soul. Basically, they’re just small and mean and not very cute, and I’ve never been a fan. In hindsight, I’m not sure why I thought going into the monkey rainforest would be a good idea, except, hey, look at the dirty monkeys. Anyway, the reality is that this little sanctuary is more like a ghetto. Admission to the primate ghetto costs 20,000 rupiah, and if you wanna feed the little assholes, it’s another 10,000 rupiah for a bunch of bananas. Casey and I opted for entry and observance, but Mat got a little more involved. By getting involved, I mean getting rabies.

The result of Mat’s puncture wound, which was inflicted by a very large, aggressive male monster, was two weeks worth of rabies shots, one tetanus shot, and several series of antibiotic treatments. Still not sure if Mat has rabies or not though, because a few of his shots and antibiotic treatments were administered later than recommended being that he flew all the way to Lakey Peak on Sumbawa, which is basically the jungle. Surprisingly enough, rabies shots are not easy to come by in the jungle, and he had to spread the word across Sumbawa and Lombok in order to find a witch doctor or something who could go to Bali and get the proper meds. He’s probably foaming at the mouth right now actually…

On the other hand, the rest of Ubud can be quite nice if you stay away from the rabies. The streets are lined with art galleries, sculpture studios, wooden statues, nicely decorated restaurants and all kinds of colorful, pretty souvenir shops. The sidewalks are crumbling to pieces and the hills are steep, but it’s definitely a class above Kuta. The place we stayed in, called Argosaka, was also much more charming than Suka, and considerably cheap for being situated in a large, quiet garden, although I suppose it was cheap because it was located so close the rabies forest. Anyway, the Ubud scenery was pretty and quiet, and we even got watch the sunrise from the top of a volcano. The sunrise thing wasn’t exactly effortless, but it was worth the near death experience.

You see, in order to watch the sunrise from the top of a volcano, you first have to get to the top of the volcano. It’s a three hour process that beings at 3 a.m. First, you have to drive to the volcano, which is only accessible by teetering on the edge of a cliff for an hour as you wind your way down a narrow, gravel road. Once you get to the volcano, you have to climb it. This is another two hours of cliff teetering. Now, it’s hard enough to hike up a steep cliff composed of dirt and crumbling gravel, with nothing but your running shoes and your camera bag, but we had to do it in total darkness. With nothing but a dull flashlight to lead the way, we trekked up the jagged, ragged avalanche of rocks with fingers crossed: please don’t let me die.

I have to say though, trekking in the dark was just as amazing as it was terrifying. Every now and then we’d stop for a few seconds, and I would look up to the sky to see more stars than I’ve ever seen in my life. The stars were dripping down the horizon as far as the eye could see, making more of a sparkling dome than a ceiling. It was the kind of sky Brandon Boyd sings about in “I Wish You Were Here,†a diamond canopy. The most surreal part about it though, was the line of flashlight orbs from the other hikers. There must have been 30 people hiking this volcano, all separated into small groups moving at different paces. While the rest of the world was a black void, all I could see in front of me were glowing white orbs, floating up, up and away into the darkness. It was like something out of a Stephen King film, watching these little lights ascending toward the stars

Though these stellar moments made a lasting impression, they seemed to be few and far between, as I spent most of the hike fearing for my life. Every now and then, I’d shine my flashlight to my right or left only to find myself on the side of a gaping cliff. Usually, right after realizing how easy it would be to fall to my death, I would try to grab onto a nearby rock to better balance myself, and the rock would come loose and start a mini-avalanche. Then my feet would start sliding on the loose gravel, and I would nearly die. Even when I was successfully balancing myself and climbing steadily, there was always someone in front of me, sliding backwards, flashlight beam flailing, ready to plummet to their death and threatening to take me with them. Usually, it was Casey. Eventually she and our designated guide fell behind, and then it was strangers threatening my life. At one point I remember hoping that if I did end up falling down the volcano, and I would at least land on my back so I could die watching the white orbs float up to the stars. I’ve found that a lot of my thoughts in Indonesia begin with, “If I die now, I at least hope…â€

Death is just not the kind of thing they warn you about when you sign up for these tours. In face, these Indonesians booking tours will say just about anything to get you to buy a ticket. When we booked the volcano sunrise, they told us it would be an “Easy walk, easy walk. Bery easy for you, no problem.†It was definitely not easy, and there were many problems. But then I really can’t complain because I met a few other travelers who struggled three-fold. My hike lasted two hours each way, and I thought that was rough, but I met two girls who spent three days hiking, 7 hours each day. They said it was one of the hardest, worst experiences they’d had in Indonesia. One girl had a cast on her wrist, and the other girl was sporting bruised ankles. “We asked them how tough the climb was and told them we didn’t have hiking experience, and they told us it was a ‘bery easy walk.’ If we’d known how hard it would be, we never would have done it. It was miserable.†I met two later met two more girls who said the same thing about the same hike, and neither one of them made it to the top. They both gave up on the second day. Rather than their guides bringing them back down to the bottom, they left them for dead and said, “You go back down, wait.†Guess I can’t complain. Plus, if the sun is rising or setting and I’m there to see it, death is just a sidenote.

Oct 10, 2011 Plastic Paradise

Let me preface my trip to Gili Trawangan with this article from The Associated Press, on September 20, 2011. 11 dead as boat sinks off Indonesia’s Bali island: “BALI, Indonesia – Indonesian police say a wooden boat carrying dozens of Balinese musicians has sunk in high waves, killing 11 people. Rescuers are scouring the waters for 14 others still missing, including the captain. Col. Agus Doeta Soepranggono says members of a traditional percussion troupe were heading Wednesday from Bali to the nearby island of Nusa Penida to perform at a cremation ceremony when their vessel capsized a half-hour into the journey. Accidents at sea are common in Indonesia, the world’s largest archipelago nation with more than 17,000 islands, in part because of overcrowding and poor safety standards.”

First of all, I’m not even sure why I decided to subject myself to the Gilis again. After my first trip, Gili T is the last place I thought I’d end up, but such is life. So anyway, to get to this plastic paradise, you have to go by boat, end of story. You can’t take a ferry, and you can’t go by plane. There are two boating options available: the more expensive “fast boat,†which I took last year, or the inexpensive “slow boat,†which I opted for this year. Never opt for the slow boat. When you opt for the slow boat, you’re actually signing up for a whole series of sluggish, shoddy transportation methods that will turn your day into one big, terrifying waste of time. It’s not simply a matter of going in a speed boat versus going in a sailboat. It’s a matter of taking a two-hour trip directly to the island, or going on the standard 5-hour ferry to Lombok, driving another hour and a half to another obscure harbor and then slowly floating across the sea in the general direction of Gili T on a piece of plywood, which takes about 45 minutes.

The ferry is one thing, but the piece of plywood is another. I’m talking about the traditional Indonesian boat. The long, skinny wooden ones, all hand crafted and dripping with splinters. They’re everywhere and they seem to stay afloat more often than not, but as the Associated Press has told us, accidents at sea are common in Indonesia, especially on overcrowded boats with poor safety standards. Essentially, this the epitome of the final leg of the slow boat journey. While most of the traditional boats have two skiffs on either side to give the boat some balance, the boat in question had none. In other words, it had no balance, no life support, no protection from capsizing whatsoever. And then there’s that whole overcrowding issue. To my knowledge, which comes from brochures, ticket stubs and harbor signs, the maximum load for one of these boats is 25 persons. Our boat was jammed with at least 35 people and a few hundred pounds of cargo.

I didn’t even have a real seat. I had to crawl over people and cardboard boxes filled with glassware and noodles, and squeeze myself into an empty space on a rotting wooden bench that was covered with mud. To avoid a dirty, splintery bum, I ended up hanging off the edge of the boat and holding on the roof like the locals instead.

The first few minutes were pretty standard I guess. Boats rock. It’s just what they do, especially when there are waves. Boats that rock too much however, capsize. Our boat was rocking too much. After about 5 minutes of standard side-to-side movement, the swell started to grow and side-to-side turned into more of a roll. The motor would come out of the water and the boat would change direction, rolling to the side or just plain dipping into the water. That’s right, water was entering the boat. This only happened a handful of times, and it was nothing major in the end, but at the time, it was a death sentence. I was absolutely certain that the boat was going under. I’d taken off my back pack, located a life jacket and was ready to swim for it. My adrenaline was pumping, my hands were sweating and I was ready to fight for my life. Casey was sitting across from me, almost in tears, her head in her lap. To make things more fun, everyone else was apparently calm. The locals had zero expression, including the guy steering the motor as it was bobbing in and out of the water. Normally this would have comforted me, but the fact that a boatful of locals just drowned under similar conditions didn’t give me much faith in their judgement.

The other foreigners either had their eyes closed or their heads down, looking calm but probably inwardly panicking. Except for the man sitting next to Casey, who said he wasn’t panicking because he just “accepted it for what it was.â€

This twenty-something Australian proceeded to tell us about the dead body he found washed up on the beach just one day prior. That’s right. This guy was soaking up the Indonesian sun, enjoying the salt and sand when a body casually rolled in with the tide, and now he was sitting here telling me that he was just “accepting the situation†and didn’t feel the need to panic. For the next 30 minutes, the boat continued to rock and roll out of control, taking on water here and there, while I sat on a box of glassware, shaking with fear and adrenaline, picturing my lifeless body drifting through the ocean.

And then we arrived at Gili Trawangan. For the next three days all I could think about was the fact that we would have to make that trip all over again. It was the only way to get off the island. I tried to convince myself that the trip here was standard procedure. The locals knew what they were doing. They knew what kind of load the boats could handle, and what kind of swell they could tolerate. The boat that capsized was probably just a victim of a rogue wave, some kind of freak accident.

The trip back to Labuan Lombok put that theory to rest. As stated on the brochures, tickets and harbor signs, we adhered to the passenger guidelines, counting heads and splitting the load accordingly between several boats, so as not to exceed 25 persons. There was no extra cargo, just an abundance of life jackets and empty space. Basically I was lucky to be alive after that first trip to Gili T. On the other hand, it was probably the most exciting part of the trip.

Gili, Shmili

I’ll just sum up my second visit to Gili T in a few short bullet points:

- Gili T is more plastic now than ever before. Not only do the resorts and tiki bars wrap the whole island now, but they are bigger, and more unnecessary. I’m talking about two-story cement structures with massive swimming pools and over-extravagant bungalows. The prices are even more jacked up, and you don’t get what you pay for.

- There’s still nothing to do, but now it’s not even relaxing. You used to be able to lay out on the beach and read a book without being bothered, but now there’s so many people you have to basically lay on top of someone if you want to sit on the beach. Quiet sunsets and bike rides are out of the question too because the whole island has been built up with resorts and tiki bars.

- The nightly entertainment is still below average. Night clubs and pubs and restaurants still blast Jack Johnson and the Black Eyed Peas. There are party lights and poorly placed speakers littering the beach. Lot’s of drunk couples making out and groping each other in the dark.

- The people are still weird and it still freaks me out. The locals are so friendly it’s creepy, and anyone who comes to Gili and enjoys it is also a creep. In general, the vibe of the island is just unnatural.

- Feral cats are still running the place. Their tails seem to have gotten a little longer, but they’re still pretty nubby compared to normal cats. Just like last year, there was one little guy who was photo-worthy. This one hung around outside of our room, and we named him Mange.

Basically, if you enjoy freaks and creeps and overcrowded beaches, if you’re a fan of Nickelback and Fergie, if you’re boring enough to like snorkeling, if you’re the kind of person who doesn’t mind paying people to like you, then knock yourself out. You’ll love it here.

Oct 12, 2011 Komodo Country

Oct 18, 2011 Catch ya later, Indo!

Get Social

Looking for Something?

Recent Posts

- Walk With Me November 21, 2018

- ASS: 8 – Hallo-What November 2, 2017

- ASS: 7 – Mullet Mobiles & Utes October 17, 2017

- ASS: 6 – Creatures June 24, 2017

- ASS: 5 – R Displacement June 19, 2017

- ASS: 4 – Australian Accents June 12, 2017

- ASS: 3 – Toilets May 29, 2017

- ASS: 2 – Test Cricket May 21, 2017

1 Comment. Leave new